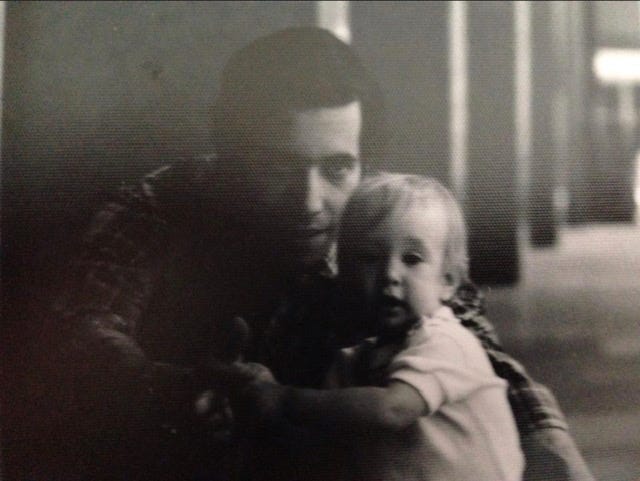

My father died when he was fifty years old and I was nineteen. He died suddenly and then slowly—a heart attack at work that he never regained consciousness from, followed by three weeks in a coma on life support, and then gone. The loss of my father changed me. It defined me for a long time. It was my identity, how I thought of myself. There was a life that my father didn’t get to live. There was a life with him that I didn’t get to live. His loss is bigger, yes, but mine...mine is big, too. And deep. And at times over the decades since, all-consuming.

I was a writer before he died, but not a fiction writer. I was that delightful/dreadful creature, the teenage poet. My poems, while my father was alive, were about sex and sweat and music and boys with mohawks. After he died, I barely wrote at all for years. When I did begin to write again in my late twenties, I found that fiction was a better fit. I was still interested in sex and sweat and music and men who used to be boys with mohawks, but all of that was just the backdrop for stories about grief and profound loss.

I hadn’t been writing fiction for very long at all before I began my first novel. Like many first novels, it was autobiographical. It was about a thirty-year-old woman walking around Park Slope and feeling sad and fucked up about her father’s death years earlier. It was my MFA thesis, and worked well enough to land me an agent, but not well enough that it got published. (Plenty of excellent novels fail to get published. This was not one of them.)

That novel, Drowning Practice, was my first dead dad novel, but not anywhere near my last. I finished that novel in 2005, and have been chasing after the Platonic ideal of the dead dad novel in my head ever since. I wrote it in different forms, with different plots and different characters. I ditched the autobiography as much as that is ever possible. I came at it from so many different angles and I just couldn’t quite get it there. (My metaphorical drawer is very full, friends.) Until my latest finished novel, that is. The one that my agent is currently shopping around to editors. The Narrow Place.

I’d been trying to fit my enormous loss, my entire wounded identity of The Girl Whose Dad Died Young, into the shape of a novel for the longest time, even when I didn’t realize that’s what I was doing. The work was dark, all of it dark. But when I finished The Narrow Place, I felt something in me come to rest. The new novel that I’m writing now has some darkness in it, because there are human beings in it, but mostly it’s a fun romp, a sort of mystery novel. Writing doesn’t feel like an exorcism this time, or like shaking a bag of pain out onto the page.

(Fun. A romp. Who am I? It’s the strangest feeling...)

What worked for me this time, what had been missing all along, is nothing I would have ever predicted. This is not to say that this is what all novels that deal with grief are missing, but this is what my novels that dealt with grief were missing: the divine.

It was a close call. I almost blew it this time, too. When I sent an early draft to a trusted reader, she pointed out that I spent the first half of the book setting up the possibility of magic and mysticism and spirituality, and then spent the second half of the book systematically shutting that down and explaining it all away. She was totally right. I’d lost my nerve. It felt too vulnerable, too scary to allow for the possibility of the existence of God, and so I shied away from it. But I was writing about death! How do you write about death and not ask questions about what happens after death? So I did the brave and scary thing and revised to reopen those doors that I’d slammed shut in the earlier draft. What a radical concept in 21st century literary fiction: A book that believes in God. But there it was. And it made all the difference.

All of that grief with nowhere to put it wasn’t good for me and it wasn’t good for my novels. Without the possibility of the divine, there was nowhere for my characters to go. Their dead fathers were just gone. Forever, utterly, irreparably gone. But allowing for the potential for something else, for something more? That opens things up in a different way.

If you asked me when I first sat down to write The Narrow Place if I believed in God, I would have told you, “No, I don’t. I do believe that we’re all made of and connected by the same energy, but I don’t believe in God.”

Now that I’ve written the book, if you ask me if I believe in God, I’ll tell you, “Yes, I do. I believe that we’re all made of and connected by the same energy. I believe in God.”

This was beautiful. And helpful to read for me as I work on a new project that is partway made of grief, but not all the way.

Oh, Cari, yes—the divine carriage through mitzrayim. I can’t wait to read it and hopefully hear you read from it.